Photo by Rhododendrites (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

I am unashamed to admit it: I am terribly proud of my people.

To what "people" am I referring here? To doctors? To scientists? To astronauts and aspiring astronaut-types? I'm surely proud of all those people. Today, I'm referring to another group to which I belong; to something I've done on and off for more than half my life; to one of the most important things I've ever done, as well as one of the most important things that occurs in a truly free and democratic society. I am referring, of course, to the press.

My people - journalists - are amazing. We bust in doors behind which lie nefarious activities that undermine the basic tenets of our civil liberties. We point the spotlight on violations of human rights. We call "foul" when justice isn't being served and, in that sense, are our own sort of justice. Therein lies the agony and the ecstasy of the media: with words, sounds, and images, we convene trials, summon the accused, calls witnesses, and cause judgments to be made. Like an outstanding attorney, an excellent journalist solicits input from relevant experts and arranges concrete evidence in such a way that the jury - our audience - can make an informed decision. In outstanding journalism - not editorial, just plain ol' features about life and the people who live it - there's no need to prosecute or to defend. The facts, well-presented, do that for themselves. The facts, poorly presented or not presented at all, twist and maul the truth and raze our ability as professionals to educate, empower, and vouchsafe civilization.

Photo By Txbeaker [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

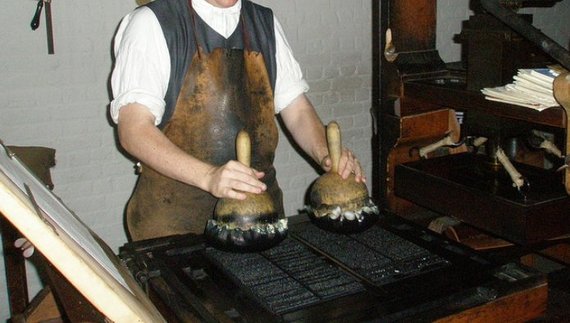

These days, both facts and the way in which they are presented are more malleable than ever. When I first got into the field, it wasn't so. Back then, I inked an honest-to-god press. The thing was a behemoth - a giant born from the black depths of global mechanization. You basically had to wrestle it in order to get your paper out. Every word you fed into that thing you thought about. Then you thought about it twice and twice again, because lord knows you didn't want to go more rounds with that infernal machine than was absolutely necessary. My summer at The Otter Valley News and Views is witnessed by the ink particles still embedded deep within the lining of my lungs.

Photography used to follow a similar plodding, dedicated to-the-point-of-cultish course. At The Daily Californian, we photographers rolled our own black-and-white film, ran up and down at sporting events at nearly the same pace as the players, and worshiped the smell of fixer in the morning- or at least pretended to, because what we sweated (and sometimes bled) for mattered. Our shots were a critical part of the process. They provided more than just meaning and context. Photographs printed on paper drew people in: they gave the words our colleagues penned the opportunity to inform readers and transform the world for the better. That was before I graduated from college, before I built something that flew into space, before I ever laid hands on a patient. Long before I ever saved someone's life, through journalism, I was able to have a significant, positive impact on the lives of my fellow human beings. And also: really great calves.

So here I am, 18 years and several degrees later, dealing first-hand with journalism from the far side of the lens. A lot has changed. For one, the cameras are now in my face, not hanging about my neck as they ought to be. The questions will be coming my way. In 48 hours, my exit from "Mars" will be attended by 55 members of the media (and my brother, who has promised to heckle me "like a reporter"). On either side of me will be five very nice, very smart, very tired innocent bystanders: my crewmates, who have born a ceaseless onslaught of media for the last 12 months with an impressive amount of grace.

In return for our patience, we've had some outstanding coverage. My most sincere thanks to VICE, The History Channel, The Surge, BBC Stargazer, The University of Rhode Island, The British Journal of Medicine, Radio New Zealand, Voices from L5 and many others for your thoughtful, thorough, and accurate pieces. We've also had our share of "What the heck is this? We don't play xBox! No one has actually been chosen to go to Mars! As for sending robots ahead of time to build our shelters for us... it's a cool idea, but not, as some people would have you think, "a done deal." Those last two informational travesties resulted from what increasingly passes for reporting: taking a story written by someone else, distilling it (badly), sprinkling it with Googled facts, and passing it off as news.*

Here we arrive at something else that's changed since that fateful day when I talked my way into a job shooting mayoral candidates, house-fires, extra softball innings, and other natural disasters for a living: As much good journalism as there is (more than ever, really), really bad media abounds.

What's the disparity between good journalism and...not? Here's my view: a journalist gathers and contextualizes information such that readers can imbue it with social relevance and personal meaning. Making up facts, distilling other peoples' articles without adding value, and lifting quotes from blogs posts rather than conducting interviews is not journalism. It takes up space in news feeds, but it isn't news. Predigested and filling, it lacks mentally nutritional value while giving readers a serious case of brain gas.

True, there's always been fluff out there. Also true: like the scarlet letter, sensationalism used to be highly visible from a distance (and for the same reason). Clearly marked by cheap newsprint yellowing before it even hit the stands or by super-glossy covers with garish titles, these tabloids practically glowed when held against a dark background. If you wanted news, you had to pluck off your doorstep or out of a metal box at a busy intersection.

These days, good journalists and bad media are jammed into the same space. No books, no covers: just the great equalizer of pixels on a screen. In the digital age, the friendly labeling we once counted on to help us discriminate between medicine and poison - between information and aggrandizement - has faded away. A text from your mother and a text from a scammer claiming that your mother is in the hospital and needs $10,000 for a procedure appear exactly the same way on your phone's LCD. An opinion piece written on an iPad on the way home from work may look as, or more, legitimate than a Pulitzer-winning piece of investigative reporting. On the surface, these two often appear the same.

That's one major change since I got into this business in 1996. The other is that properly trained, properly-paid journalists are vastly outnumbered by people under deadline to write click-bait.

So: what's a simulated astronaut to do?

Fundamentally, my job, whether I'm an astronaut or a reporter or a doctor, is to make things work: to take the limited resources at hand and deliver a victory for the home team. Ship me anywhere in the 'verse. Make the delay 20 minutes, 200 hours, or 40 days and 40 nights. Whatever the apparent barriers, I won't abandon my people - many of whom are or could be good writers who aren't given the time or training to make their product what it rightfully should be. I can't change that right now, but I can help even the odds stacked against us all by expediency, mediocrity, and inertia.

On 8/28 you will be able to ask us any question in the world. To help even the odds, here's a list of questions we've already answered many, many times:

- What have you learned?

- What do you miss?

- What did you eat?

- Have you seen The Martian?

- How did it feel to not have the Sun and the wind in your face for a year?

- What's the first thing you're going to do?

- What's been the biggest challenge about being on Mars?

- Do you guys argue? How do you deal with conflict?

- What do you do if someone gets sick?

- Have there been any disasters during the mission?

- Do you really want to go to Mars?

- Did this mission - do any simulations - help pave the way for the human exploration of Mars?

- How is this simulation different from Mars?

- How did your families react to your decision to go into isolation?

- Did you always want to be an astronaut?

- Have you ever felt like quitting?

- What will be the hardest part about coming back to Earth?

- Would you do it again?

- Are any of you signed up for the one-way trip?

We're very glad that people are curious enough about our mission to ask any question that comes to mind. At the same time, anyone locked in a box with no direct access to the outside world, no fresh food except the small amount that they can grow in whatever space they aren't sleeping on, and only five flatmates can easily imagine what they are going to miss: more friends, family, sunshine, wind, flowers, pineapple, sushi, long walks in the woods, and tailgating at Cal games (go Bears!). If "What do you miss?" was a mystery, thanks to the power of Reddit, six crew blogs, and countless news articles, that mystery has been solved.

To my fellow journalists out there: there are much better questions to be asked and answered. For the record, the questions that were truly mysterious until I arrived on "Mars" and have never/rarely been asked by the media are:

- What turned out to be replaceable? What foods were replaceable, or even better/easier to make? What new favorite food took the place of the old one that you can't have?

When we ask the right questions, we get people thinking, challenging assumptions, and pushing the boundaries of what ought to come next. These are free from me to you. Go to!

We Martians are ready to meet the press. We've been getting ready all year. All that we ask in return for the time that we're giving you the minute we hit dirt - I have to let you photograph me before I can so much as hug my husband - is this: be journalists. Be the truth-advocates who held this country together for hundreds of years. Adventurers like us are always good for a story. We scientists have been keeping things interesting for the last few centuries. Astronauts - bright and shiny! - are the new kids on the block when it comes to popular coverage, and deservedly so. We've faced dangers and made sacrifices for twelve long months, and we thank you for your attention. So please, come one and come all to the show. And when you come, bring the right questions. When the hatch opens and we finally present ourselves to you, that's the signal: It's YOUR turn to be the hero. To write our way into the future. To find the facts, solicit the opinions, and frame the stories that will make the last year - our lives in service to science and Earth and all of humankind - meaningful. To make the fact that I waited 366 days PLUS 10 minutes to hug my husband worthwhile. So let's do this, people. We scienced the heck out of this. Now, let's write the heck out of this.

You ask. We'll answer. Make me proud.

Courtesy of Wikimedia commons, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=197374

*Corrections were requested to all of these articles.